SYNTHES ANALOGIQUES: Les raretés!

- 2 402 réponses

- 168 participants

- 349 871 vues

- 176 followers

oryjen

Je commence avec cette page stupéfiante:

http://www.synthmaster.de/mus.htm

A vous les (home) studios!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

L'artiste entrouvre une fenêtre sur le réel; le "réaliste pragmatique" s'éclaire donc avec une vessie.

Anonyme

Ça me rappelle quand j'ai passé le code

oryjen

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

L'artiste entrouvre une fenêtre sur le réel; le "réaliste pragmatique" s'éclaire donc avec une vessie.

[ Dernière édition du message le 25/05/2020 à 10:36:54 ]

kosmix

Putain Walter mais qu'est-ce que le Vietnam vient foutre là-dedans ?

Neveud

Kosmix je ne te comprends pas! suis à 2 doigts de pieds de te coller -1

aujourd'hui je reste couché / tout a déja été fait / rien ne disparait / tout s'accumule (dYmanche)

[ Dernière édition du message le 26/05/2020 à 03:09:05 ]

kosmix

Nan mais OK pour les ingé-son hipsters c'est le top du top dans le studio, avec quelques traces de rouille tu as le gros son authentique

C'est probablement une chouette machine

(une fois désinfectée)

Putain Walter mais qu'est-ce que le Vietnam vient foutre là-dedans ?

[ Dernière édition du message le 26/05/2020 à 03:20:56 ]

Analog_Keys

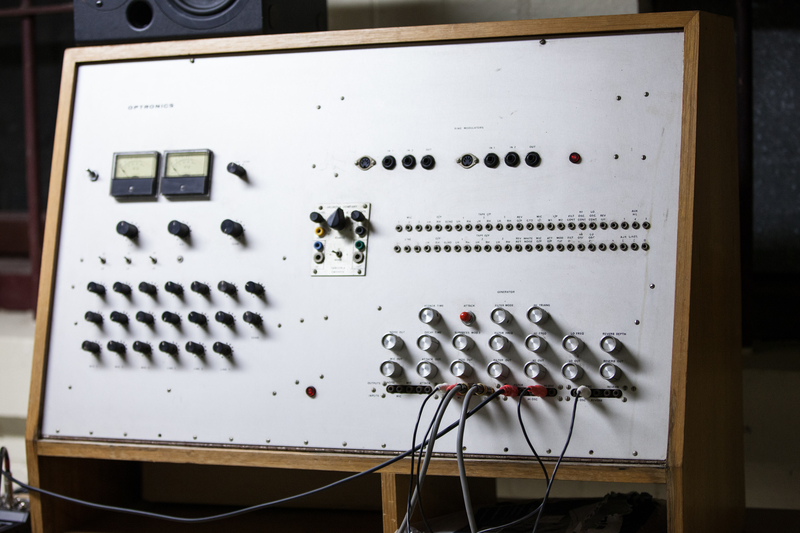

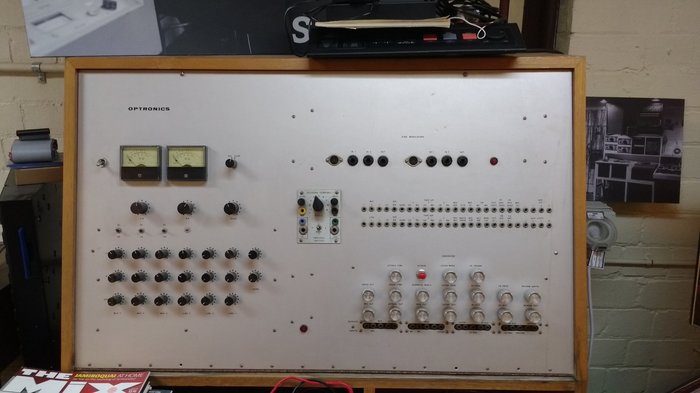

EMS VCS1:

C’est tout à fait le genre de

erewhon

Le plus majestueux des chênes n'était autrefois rien d'autre qu'un pauvre gland...

Analog_Keys

oryjen

(EDIT: non il y en a eu trois. L'image ci-dessus n'est pas un prototype, c'est l'exemplaire, intégré à un système plus large, commandé par le compositeur australien Keith Humble)

Au début EMS travaillait sur commande.

Celui-ci avait été commandé par le compositeur australien Don Banks.

Ici l'histoire de cette machine (en anglais et en spoiler parce que c'est assez longuet!):

3. THE DON BANKS MUSIC BOX

The basic story of the Don Banks Music Box has been recounted by Cary (and others) in print and in interviews in various media, with minor variations (e.g. Cary 1992: xxv, 2006; Bate 2006). However, the nearest to a contemporary account that I have come across so far is Banks’s own, from 1972. His story of the instrument’s origin runs like this:

when spending an evening with Peter Zinovieff I complained bitterly about the lack of facilities for composers to learn the language of electronic music. Peter, as generous as ever, said he would ask David to design a kind of instrument which would incorporate a number of facilities which one would need to know about in the production and treatment of sound. 3 Weeks [sic] later I had a grey box […] which incorporated all the basic principles. At the time it was known as the ‘Don Banks Music Box’. Actually three were built and are still in use. (Banks 1972)

There are two things to note here. First, Banks says ‘At the time it was known as the “Don Banks Music Box”’ (hereafter DBMB). I shall return to this point later. Second, he mentions that three units were constructed. The other two units eventually went to Lawrence Casserley, then Cary’s student at the Royal College of Music, and Banks’s Australian friend, the composer Keith Humble (Figure 2). 5

Figure 2 Keith Humble’s synthesiser (c.1968) built into a larger unit by Graham Thirkell and now in the collection of MESS Ltd, Melbourne. Photo: James Gardner.

It is also worth noting that the DBMB’s design specification did not come from Banks himself. According to his 1972 account, he deferred to Zinovieff and Cockerell as to ‘which facilities […] one would need to know about’ – note the imperative. It could be argued, then, that one of the main determinants of the DBMB design was Zinovieff and Cockerell’s opinion of what a composer ought to find useful.

Another determinant, of course, was Banks’s budget. Tristram Cary’s accounts of the genesis of the DBMB are similar to those of Banks, but Cary consistently claims that Banks came to ‘us’ – rather than Zinovieff alone – and that his price limit was £50, rather than the £100 that Banks once recalled (Banks 1977).

Cockerell’s account suggests the DBMB was made partly to assess the appetite among musicians for such a device: ‘I just put together various bits and pieces that I’d previously built for Peter and put them in a self-contained box to see if musicians would find any use for it’ (Cockerell 2010). It would be a stretch to see this as ‘market research’ but it does hint that Zinovieff was testing the water for a commercial product at this early stage.

In later interviews and articles, Cary asserted that the DBMB was called the VCS-1, positioning it clearly as the first device in a consciously numbered series culminating in the VCS3. In this sense, Cary could be seen to be guilty of the ‘linear’ approach disparaged by, inter alios, Pinch and Bijker. I have, however, found no use of the term ‘VCS-1’ that pre-dates the release of the VCS3, and I would argue that the ‘VCS-1’ name for the DBMB was applied only retrospectively; well after the VCS3 name had been adopted in the second half of 1969. The earliest use of the term ‘VCS-1’ I have found thus far is in a letter from Banks to the New Zealand composer Douglas Lilburn, dated 30 August 1970 (Banks 1970a).

Lawrence Casserley’s unit does not actually say ‘VCS-1’ anywhere. Rather, it is labelled ‘Electronic Music Studios Sound Synthesizer’ in Letraset. Casserley is adamant that the label was already on the device when he picked it up in spring 1969 from Delia Derbyshire, to whom it was on loan (Casserley 2015a). At the time, it had been in the Camden studio of Kaleidophon – the company name under which Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson and David Vorhaus were then working. The circulation of this particular DBMB can be seen as a kind of beta-testing on the part of EMS by potentially interested colleagues or acquaintances. None of these, it should be noted, was directly active in the popular music field, though Derbyshire and Hodgson did associate with figures from the contemporary underground and countercultural art scenes. Asked about his first encounters with the DBMB and VCS3, Hodgson reflected on the loose professional and social networks of the time:

I seem to remember Peter mentioning Don Banks and things like that. One was just on the scene – it’s hard to explain the complete informality of the way life was in those days, in the ’60s. Nowadays everything’s cut and dried. In those days we were all wafting around. […] It was much more informal – a whole lot of relationships were. […] Tristram was around quite a lot, and he was a good friend of Delia and me. And so in a way a lot of the communications that went on with EMS would go through Tristram. (Hodgson 2014)

The informal knowledge-sharing that was common among electronic music practitioners of the time is also illustrated by the handwritten instructions and notes that Banks prepared for Keith Humble to help him get to grips with his DBMB (Banks 1969) – notes that in turn amplify Cockerell’s original instructions to Banks (Cockerell 1968).

If we regard the DBMB as a convenient and cost-effective collection of devices that David Cockerell assembled for Banks, we have to ask how this specific collection was arrived at. A definitive answer to that question is impossible at this distance, but it seems likely that Zinovieff and (probably) Cary drew on their combined experience as electronic music practitioners and conferred about the most useful devices. This, of course begs the question: useful for what? The point here is that the criteria behind this choice are not simply technical or pragmatic, but also aesthetic. As I noted earlier, we could characterise Cary and Zinovieff’s standpoint with regard to electronic music as post-war modernist, seeking to create a new music from the raw materials of sound, freed from the constraints of acoustic instruments, and thus the technological design of the DBMB is closely allied with these aesthetic, or even ideological, aims.

What features did they choose for the DBMB?

4. The Don Banks Music Box: Basic Features

1. White Noise Generator.

2. Mic. pre-amp.

3. Envelope Generator (with attack and decay controls only).

4. High Frequency Oscillator (sawtooth/triangle with variable waveshape) with a quoted basic frequency range of 1Hz to 2kHz, but greater via voltage-control.

5. Low Frequency Oscillator: falling sawtooth wave only, 25–300Hz range.

6. Filter with variable Q, capable of self-oscillation. Cutoff not voltage-controllable.

7. Ring Modulator/Voltage Controlled Amplifier.

8. Reverb.

It is worth noting that the DBMB does not offer an easy way of producing sequences of specific discrete pitches from its front panel controls, or straightforward control of pitch from an external keyboard. This is hardly hardly surprising, given Banks’s needs and Cary and Zinovieff’s aims. The patching, by means of RCA connectors, is reasonably flexible, allowing devices to be connected in many different ways; there is no normalised signal or control path. The DBMB is a compact, self-contained device designed for sound-generation and sound-processing, offering a lot of ‘bang for the buck’. Described thus, it may easily be viewed as a precursor of the VCS3, though its human interface is crude: just rotary knobs and one attack-initiation button. But it would be misleading to describe the DBMB as a VCS3 ‘prototype’: there seems to be no evidence, at its design stage, that there was a vision of a more sophisticated commercial synthesiser for which the DBMB was a portent.

From the outset, then, the DBMB was designed with signal processing and synthetic tone generation in mind. This ability to process external sounds as well as to generate them internally was carried into the design of the VCS3.

Banks was clearly delighted with his new synthesiser: ‘Thank heaven for the age of miniaturisation’ he enthused, ‘because this was small enough for me to take to bed with headphones, and to start to explore a new world of sound’ (Banks 1970b). Indeed, on a trip to his native Australia in April 1970, 6 the Sydney Morning Herald reported that:

One advantage of electronic music is that you can compose sitting up in your bed, with the aid of your Voltage Controlled Synthesiser. The V.C.S. (also known as the Don Banks Music Box) produces [… various waveforms …] Australian composer Don Banks had his electronic synthesiser specially built for him, and takes it with him everywhere he goes […] At home in Purley, near London, he takes it to bed to work out sound combinations, but uses headphones to placate his wife, who objects to electronic music at bedtime. (Jones 1970)

Banks did not see his synthesiser as the VCS3’s linear forebear. When asked whether the DBMB was ‘the beginning of the VCS3’, he answered:

Well, yes, in a very funny way I expect it could be seen as that. But it was only because I was putting the pressure on Zinovieff that … you know, there were a whole number of independent composers who needed help, who needed to be able to work at home. And I expect probably from that that [the VCS3] did start. But that was not originally … not in Zinovieff’s mind. I think it just happened that he saw there was a demand. (Banks 1977; my italics)

Banks’s assertion that numerous composers had been in the same position as him is worthy of note: there was a perceived need, and market, for such a device. Not only that, Banks credited the later VCS3 with empowering the previously disenfranchised ‘independent composer’: ‘we were able as independent composers at the time to make a start at [electronic music]’ (Banks 1977).

The DBMB, while useful, was not, in Cary’s opinion, sufficiently well-specified to be a viable commercial product, but ‘it spurred us on to dream up a more sophisticated package with features we couldn’t put into Don’s little grey box’ (Cary 2000), a package that ‘would appeal not only to composers but also to schools art music composer, but also to position the new device so it might appeal to a wider market.

" rel="ugc noopener" target="_blank"> very good teaching instrument for acoustics and so forth’ (Cary 2003).

The positive reception of the DBMB, then, led the team to consciously address in the subsequent ‘package’ not only what they perceived as the needs of the art music composer, but also to position the new device so it might appeal to a wider market.

Vous y apprendrez aussi comment et pourquoi cette équipe de bricoleurs expérimentaux s'est tournée vers la production de série

Tirée de cette page très complète sur l'histoire d'EMS:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/organised-sound/article/don-banks-music-box-to-the-putney-the-genesis-and-development-of-the-vcs3-synthesiser/38928808A05A6F2118B148CE302E3764/core-reader

Vous y apprendrez aussi comment et pourquoi cette équipe de bricoleurs expérimentaux s'est tournée vers la production de série

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

L'artiste entrouvre une fenêtre sur le réel; le "réaliste pragmatique" s'éclaire donc avec une vessie.

[ Dernière édition du message le 26/05/2020 à 08:54:44 ]

Analog_Keys

Pour info la fiche produit de l’EMS VCS1 n’existait pas ce matin sur AF...

[ Dernière édition du message le 26/05/2020 à 19:23:21 ]

- < Liste des sujets

- Charte